An Unusual Profession

At events where I accompany with graphic recording and in seminars and workshops that I hold on the topic of “translating content into images,” but also when I meet new people, it happens again and again. When I say that I draw professionally and help others present their topics in a way that resonates with the target audience, the question arises: “How does one become a content-to-image translator?”

Act 1: Why I Didn’t Study Art

People who see me drawing today usually assume that I studied something artistic. If not applied or fine arts at university, then at least some form of illustration or graphic design. And that’s what I actually wanted too. However, there was a problem. Three problems, to be precise. And all three seemed to my younger self to be carved in stone facts that I could not change.

”I’m not good enough.”

Do you know one of those kids who draw from a young age and spend every free minute with a pencil in hand, bent over a piece of paper? Those little wonder-people who master perspective effortlessly as teenagers, can draw things so realistically that one might think it’s a photo, or proudly distribute their funny comics at school and to family? I admire these little geniuses, but I was never one of them. Not even close.

I always enjoyed drawing, but I never considered my pictures to be particularly good or shared them with others. At my school (a public school with a focus on natural sciences), there were a few exceptional talents when it came to drawing - I, on the other hand, stood out neither in school nor in my family artistically. I belonged to a species that, for inexplicable reasons, was far less popular: I was one of those kids (yes, they exist) who liked math. And drawing. And cats. A combination (I refer to math and drawing) that would prove helpful in the future, but in my childhood raised no suspicion in anyone (and certainly not in me) that “Oh, that child is an artist!”. I mean, who has heard of artists who like math? Come on…

”I won’t pass the entrance exam.”

When it came time to consider what I wanted to do after school, problem number 1 inevitably led to problem number 2: I was afraid I wouldn’t pass the entrance exam at art school. Today, I would think that I can only find out if I can make it by trying, and I would just apply to see what happens.

Back then, however, the thought of being evaluated by experts who would then (in my personal estimation with high probability) conclude that I wasn’t good enough for their esteemed halls was terrifying. That would settle it once and for all: I have no talent. Black and white. Tough luck.

”I need to earn money.”

On top of the self-doubt, I knew that after finishing school, I would be on my own. My mother was a single parent. Without us ever discussing it, I was aware that I would need a job after completing my education that would pay my rent, my food, and my clothing. And with which I could one day also start a family without being dependent on my partner.

I had no role models in my environment who worked in the creative field. As a teenager, I therefore couldn’t imagine for the life of me how I would earn a living from drawing. Even if the fancy art university had accepted me.

Conclusion: Kid, get yourself a sensible job.

So I buried my dream for the time being. And at that time, it didn’t seem like a big sacrifice to me. Studying art was not something anyone had to talk me out of. In a real world with real problems - so I was convinced at 18 - drawing pretty pictures was reserved for those who didn’t have to worry about their rent.

Graphic recording and the work I do today as a freelancer didn’t exist as a profession back then. And I knew nothing about the already possible and existing professional reality of graphic designers, illustrators, or motion designers. And I wouldn’t have known whom to ask about it.

So I chose a field of study that I believed was the sensible choice and would ensure that I could definitely pay my rent: business. Because - I thought - you can always get a job with that. Which isn’t entirely wrong…

Act 2: Why Statistics is More Creative than Many Think

So at 18, I ended up at the Vienna University of Economics and Business (and for one semester in London), where I specialized in marketing management, advertising science, and market research. I chose marketing because I thought I would learn something about designing posters and advertisements. I thought I would learn the hidden tricks that television commercials use to convince consumers of a product. I should have done better research. 🙂

From Art to Mathematics

In my four years of study, I learned nothing about color psychology, storytelling, or image composition (for that, as it turned out, I should have applied to art school). Instead, what I learned was to better understand corporate processes. I read, discussed, and attended lectures on accounting, controlling, law, human resources, economic history, and statistics. A lot of statistics. But - you remember - I like numbers. I found analyzing large datasets not only exciting but also challenging for my creativity.

- How do you design a questionnaire so that you get comparable answers?

- Why is it important to distinguish between qualitative and quantitative data?

- When is a statistic distorted, even if it is fundamentally not wrong?

- How do you mathematically analyze large datasets correctly?

- What conclusions can be drawn from the data obtained?

Market research led me into the world of statistics, and after completing my studies, I ended up at an IT company, where I spent several years helping corporate clients from various industries sort their numbers. Specifically, this meant: I taught courses and helped controllers, accountants, and managers bring order to their numbers. The goal: to sort large piles of numbers into clear tables, so they could then be analyzed mathematically correctly and as automatically as possible, allowing conclusions to be drawn from them.

What I Learned from Holding Seminars and Workshops

Holding seminars was great. I learned a lot about working with groups, starting with presenting intensively using flipcharts and realizing that visually summarizing complex content immensely helps participants understand even the most complex formulas and structures and apply them to their work in practice.

Since good seminars require not only technical skills but also demand quite a bit from the trainer in terms of didactics and group management, I completed many further training courses alongside my work. Especially the train-the-trainer and coaching programs were personally very beneficial for me, because what I didn’t know back then was that for the step into self-employment, I would also need to learn to ask the right questions and listen well to my clients.

How Flipcharts Paved My Way

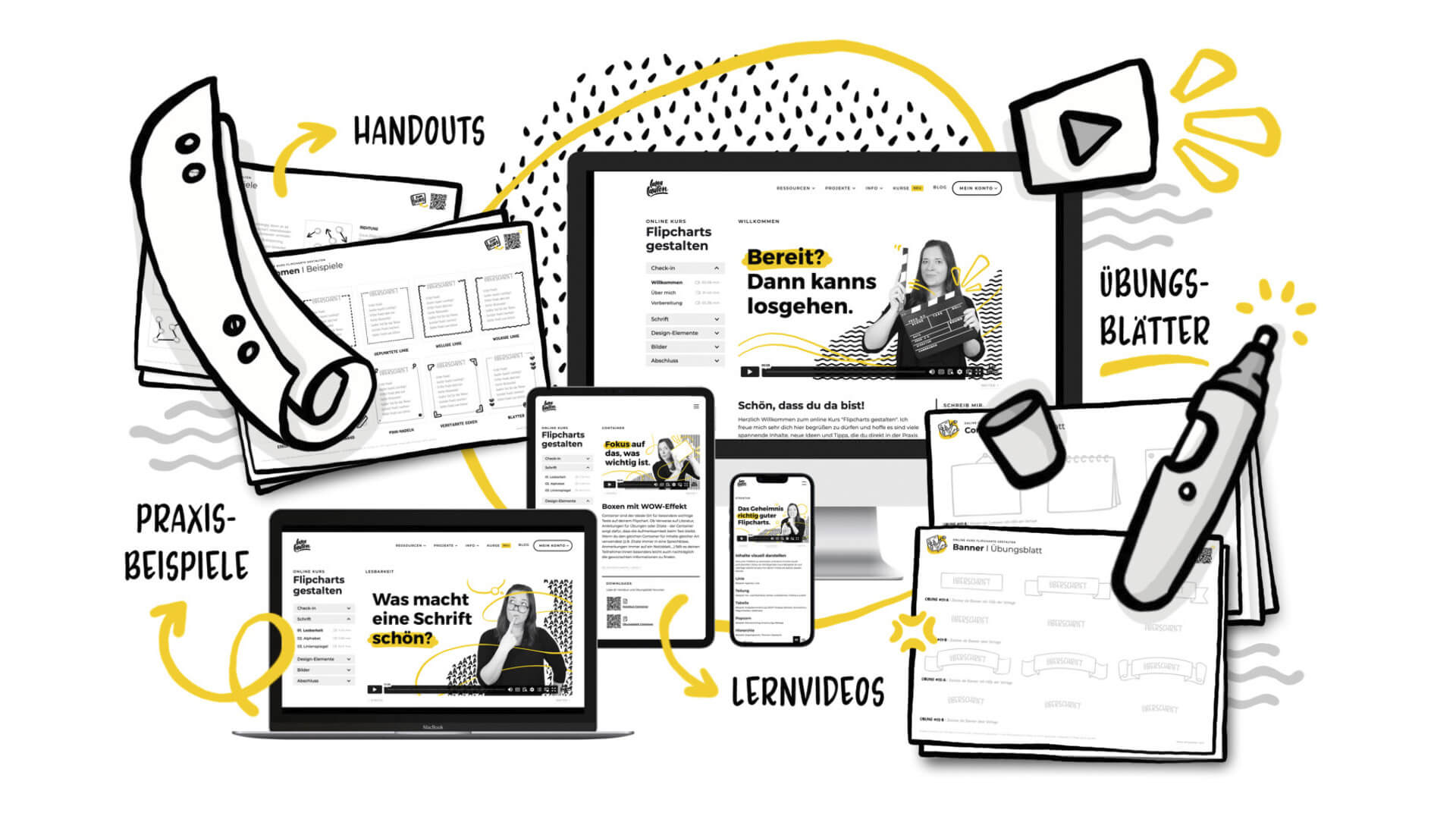

But back to the seminars: my flipcharts made the rounds. After each workshop, I created a flipchart protocol and sent it to my participants and clients. They liked it, and soon I was asked to hold flipchart design courses for my trainer colleagues. I think that was the moment when I first thought, “Ha, maybe I can still do something professionally with my drawing skills!”

The courses for my colleagues didn’t stop there. At some point, my seminar participants also started asking me if I could draw at other events to visually capture the content. I thought that sounded quite fun and enthusiastically said, “Yes, of course!” Without realizing that I would soon embark on a completely new path. Or that this “drawing along” is a new method that is currently gaining popularity in America under the name “Graphic Recording.”

Act 3: How Everything Came Together

So I occasionally sketched at events. At each event, my work was seen by new people. More inquiries came in. With each new request, my confidence grew that I was onto something. For the first time since school, I began to engage intensively with drawing again. Soon after the first graphic recordings, requests for explanatory videos followed: “Can’t you just let a camera run while you sketch?” It wasn’t that simple, but I was as motivated as a toddler whose door has just been opened to a room full of balloons and loud dance music; with trampolines and confetti rain; and a ball pit; and baby kittens… That was exactly what I wanted to do! Not the kittens - the drawing and creating of videos to help others translate complex content into images. Suddenly, all my quirky and seemingly randomly assembled skills made sense. I embraced self-employment with open arms and embarked on a new big adventure.

Yes, that’s how it was. Looking back, I believe I was very lucky. Very lucky that my work sparked interest. Very lucky that interested clients opened the door to the world of graphic recording and explanatory videos through their inquiries. Very lucky that I was recommended so diligently. Very lucky that all the paths and detours eventually came together into a big whole.

That doesn’t mean I didn’t contribute to it. I worked through nights, had to overcome many difficult situations, honed my skills, and learned new things repeatedly. I put in the effort. For my clients and for my projects. But not everything is in our hands. And for the part that isn’t in my hands, I am grateful. Very much so.

Trust Your Compass and Forget the Map

I believe you can’t plan everything anyway. I often think of the speech Steve Jobs gave many years ago to the graduating class of an American elite university (you can find the video here). He talks about how you can only connect the dots when looking back.

I would say you can only pack a compass when you set out, but not a map. A map would allow you to clearly and distinctly set the destination in advance. A map would show the gorges and mountains on the way to the goal. You would know what lies ahead and could prepare for it or even avoid the pitfalls. I believe that doesn’t work that way. There is no map that tells you everything in advance. Sometimes I wish for such a map, but somehow the journey would probably be much more boring with it.

I believe what we have is a compass. A feeling of which direction is right for us. A sense of which door is the one we want to go through, even if we don’t yet know why. And then you have to be brave and set out on the path. And fall. And get up. And hope to meet people along the way who support you. Who cheer you on when you run out of breath. Who occasionally clear a pebble from your path. Who show you the way to a bridge when you stand before a raging river or hold a towel ready when you haven’t found the bridge but have nonetheless reached the other shore, swimming and gasping for breath.

Thank you to all my door-openers, courage-encouragers, pebble-removers, path-showers, and towel-providers. Without you, I wouldn’t be where I am today, and the journey wouldn’t have been the same.

In this sense: Here’s to the next stages and adventures - my compass is ready, and I have a feeling of where it might lead…